Born with a heart defect, no one thought he’d live long. Now he’s 72

For Jim Brandon, tomorrow has never been guaranteed.

“I’ve been lucky – very lucky. And I’m going to fight for every year I can get,” Jim said.

So far, that attitude has gotten him through 72 years.

Jim was born May 20, 1947, with a congenital heart condition called tetralogy of Fallot, which makes it difficult for the heart and lungs to properly oxygenate blood.

Today, this condition can be diagnosed during a sonogram or newborn screening, but in the 1940s, Jim became what used to be called a “blue baby.” Because his blood wasn’t properly oxygenated, his lips often had a bluish color. As a toddler, Jim would take a few steps, then crouch down to rest.

“Even the least bit of exertion, I would turn blue,” he said, touching his lips.

Jim’s lifetime has coincided with the emergence of congenital heart repair as a medical specialty. Thanks to pioneers in medicine – and some luck – he’s outlived his life expectancy many times over.

A series of surgeries

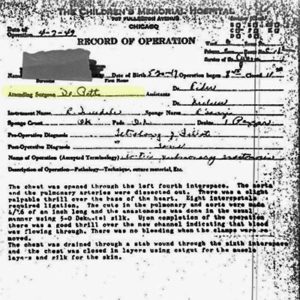

Jim’s first heart surgery was April 7, 1949, a few weeks before he turned 2 years old. He traveled with his parents from their home in a small town in Indiana to Chicago, where Dr. Willis J. Potts developed a procedure to treat blue baby syndrome just three years before.

Jim’s first heart surgery was April 7, 1949, a few weeks before he turned 2 years old. He traveled with his parents from their home in a small town in Indiana to Chicago, where Dr. Willis J. Potts developed a procedure to treat blue baby syndrome just three years before.

The family arrived at Children’s Memorial Hospital with a blue-lipped toddler and hope they could extend his life by a few precious years.

“It had to be horribly scary. My life expectancy without the operation was maybe 6 years old,” Jim said.

Jim’s parents were in awe when he graduated high school – a milestone they weren’t sure he’d ever reach. Soon after he started college, he began feeling more and more tired.

“I thought it was just part of getting older,” Jim said. But at an annual checkup, doctors told him his heart wasn’t keeping up with his growing body.

He had his second heart surgery at age 21. Again, Jim and his family hoped this would buy him more time.

A few years later, Jim was preparing to move for a job. He sat down with Shirley, the girl he’d been dating, and told her maybe they should consider going their separate ways.

He explained the complexity of his congenital heart condition, and that he didn’t know how long his heart would last. He didn’t want to be a burden to her if his heart should eventually, inevitably fail. But she rejected his argument.

“I said, ‘Well, we’ll just enjoy our time together,’ and so far we’ve had 39 years,” said Shirley, his wife.

Jim has lived his entire life with that attitude – not knowing how much longer it would last, but being grateful for every passing day.

A medical marvel

One of Jim’s most complex heart surgeries came in 1983, when he had a total correction performed at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where he’s traveled for follow-up appointments every year since.

Treatment of adults with congenital heart disease was a new specialty, and doctors who could care for a heart like Jim’s were few and far between.

Before the surgical procedures developed by Dr. Potts and others, very few children born with heart defects survived into adulthood. Likewise, few doctors had experience providing this specialized care to adults. Traveling a long distance seemed a small price to pay for the care he needed.

Earlier this year, Jim was in the hospital at OSF HealthCare Saint Francis Medical Center in Peoria when an advanced practice registered nurse walked into the room.

“I understand you’re a bit of a relic,” Kristi Ryan, APRN, said.

As part of the Adult Congenital Heart Program at OSF HealthCare Children’s Hospital of Illinois, Kristi works with adults like Jim who were born with a congenital heart condition – but it’s not often she gets to meet someone of Jim’s age and history.

“The surgeries he had were done by some of the pioneers of congenital heart surgery. He had a Potts shunt surgery performed by Dr. Potts,” she said.

While meeting Jim and listening to his unique heartbeat was an exciting opportunity for Kristi and her colleagues, meeting them was perhaps just as surprising for Jim. He’s been living with congenital heart disease for longer than the OSF Children’s Hospital program has been operating, and he had no idea that specialists were available so close to his home in Morton.

Congenital heart care close to home

The same week he was in the hospital, OSF Children’s Hospital received word it had earned accreditation from the Adult Congenital Heart Association as a comprehensive care center – a designation held by only 30 programs nationwide.

The same week he was in the hospital, OSF Children’s Hospital received word it had earned accreditation from the Adult Congenital Heart Association as a comprehensive care center – a designation held by only 30 programs nationwide.

Because of his long standing relationship, Jim will still continue to see his Mayo Clinic doctor when necessary. But now, he will also see Dr. Marc Knepp at OSF Children’s Hospital, receiving comprehensive adult congenital heart care much closer to home, so he can continue to beat the odds.

Knowing his heart was at risk from the start, Jim has always been careful to know his limits and to take a rest when he needs it.

He keeps in shape walking his dog a minimum of two miles every day. After raising two children, Jim still works in hardware and software repair, though he‘s looking forward to his retirement this year so he and Shirley can spend more time traveling and hiking.

“If my parents were to know that I’m still living at 72, they would not believe it,” Jim said. “But tetralogy of Fallot is not a death sentence.”

With the right care, it can be part of a very long, healthy life.

“You’ve always been in the right place at the right time, with the right people,” Shirley, said.